Personal libraries

They are as varied as humans themselves // externalized associative cognition // burden // decoration // social signal // intellectual proxy

One of the most common things you hear people say about books is how difficult they are to move. That’s been true as long as there have been books, but in the modern world there’s a direct follow-on: as opposed to what? The answer, of course, is PDFs, Kindles, iPads, and digitally formatted information generally.

Many people wonder whether they need physical books anymore.

I’m not going to tell you whether you need physical books, but I am going to tell you some ways I think about personal libraries, and why I have one.

What is a personal library?

A personal library is, in its most simple definition, a collection of books kept in the home. Whether it is organized, useful, pretty, or enjoyable is up to the individual. Libraries are neutral. Their adjectives are rarely inherent, and usually endowed by their owners and visitors instead.

This means that the word “library” (or “books”) actually points to many different things, because people do many different things with their collections of books, and have different intentions for them. As with any word that means different things to different people, one must take pains not to conflate all the separate instances.

So personal libraries, it turns out, are many things.

Libraries are externalized associative cognition

I keep a large personal library, especially for an NYC apartment, and I am confident most people don't fully grasp what I do with it, or what it does for me. Collections of books, especially if deliberately acquired and specifically arranged, produce emergent qualities that are greater than the sum of the individual books. These qualities reflect, and magnify, the library owner’s own ability to think associatively (which is what humans do anyway).

Let me give you an example, which I originally outlined on Twitter.

One of the first things I do when reading a book is find its publication year in the front matter. Knowing the year a book was published can completely change the way you think about its contents—it might, in fact, invert them—and you can place the book more easily in a larger historical model of the world.

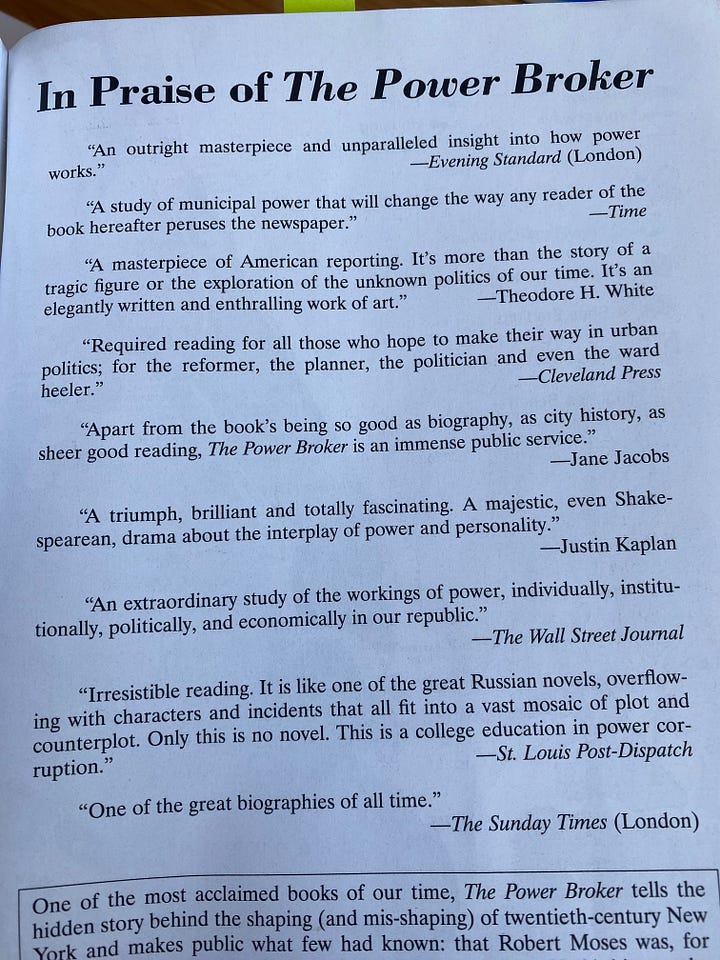

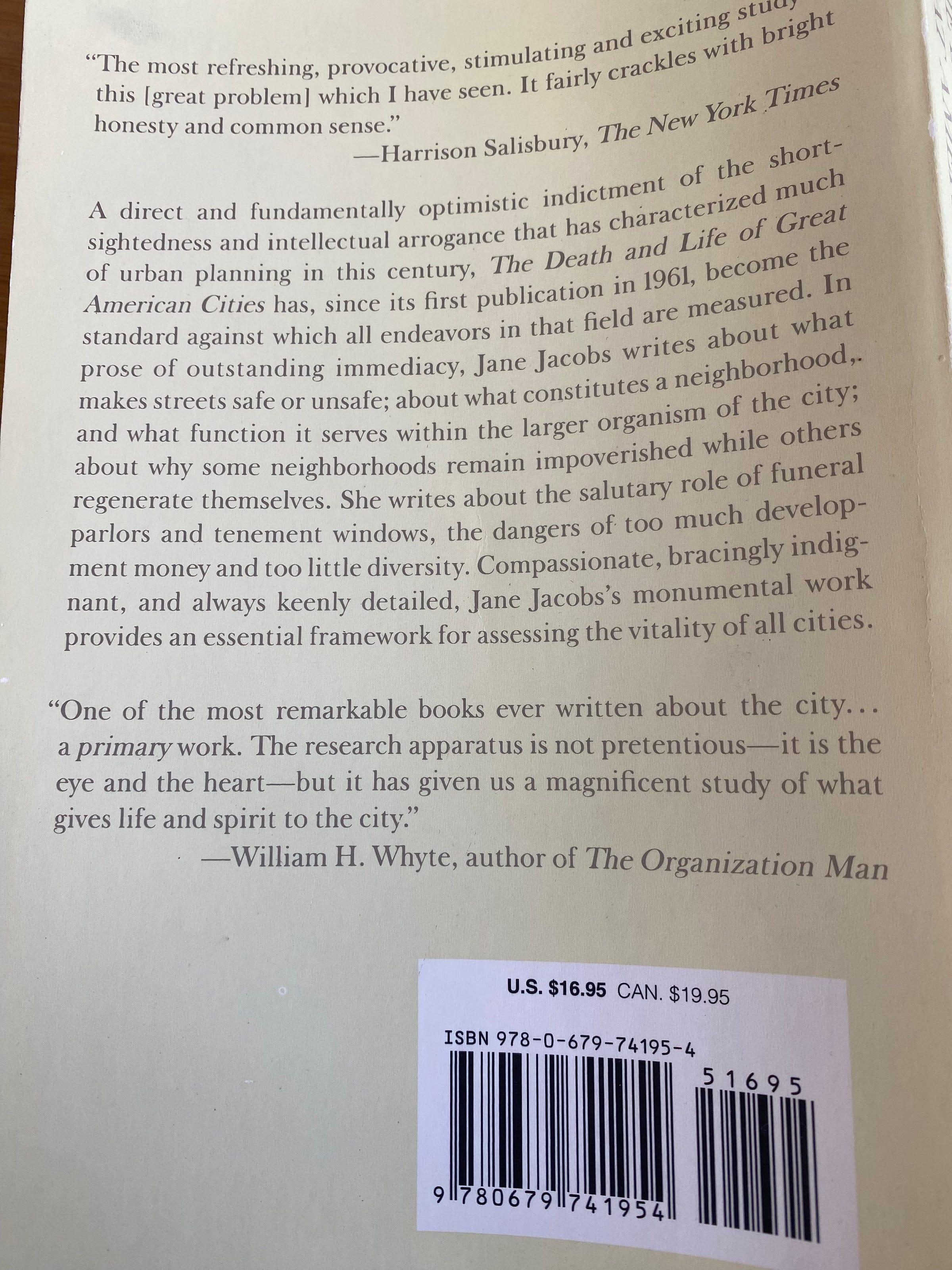

The liminal information contained within books (publication year, blurbs, and more) can often be as enlightening as the contents that the authors themselves wrote. And liminal information reveals intellectual affiliations, chains, and evaluations between different books and their authors.

Let's take a look at Jane Jacobs' The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961.1

Here's the back cover of Death and Life. Look at the last blurb by William H. Whyte.

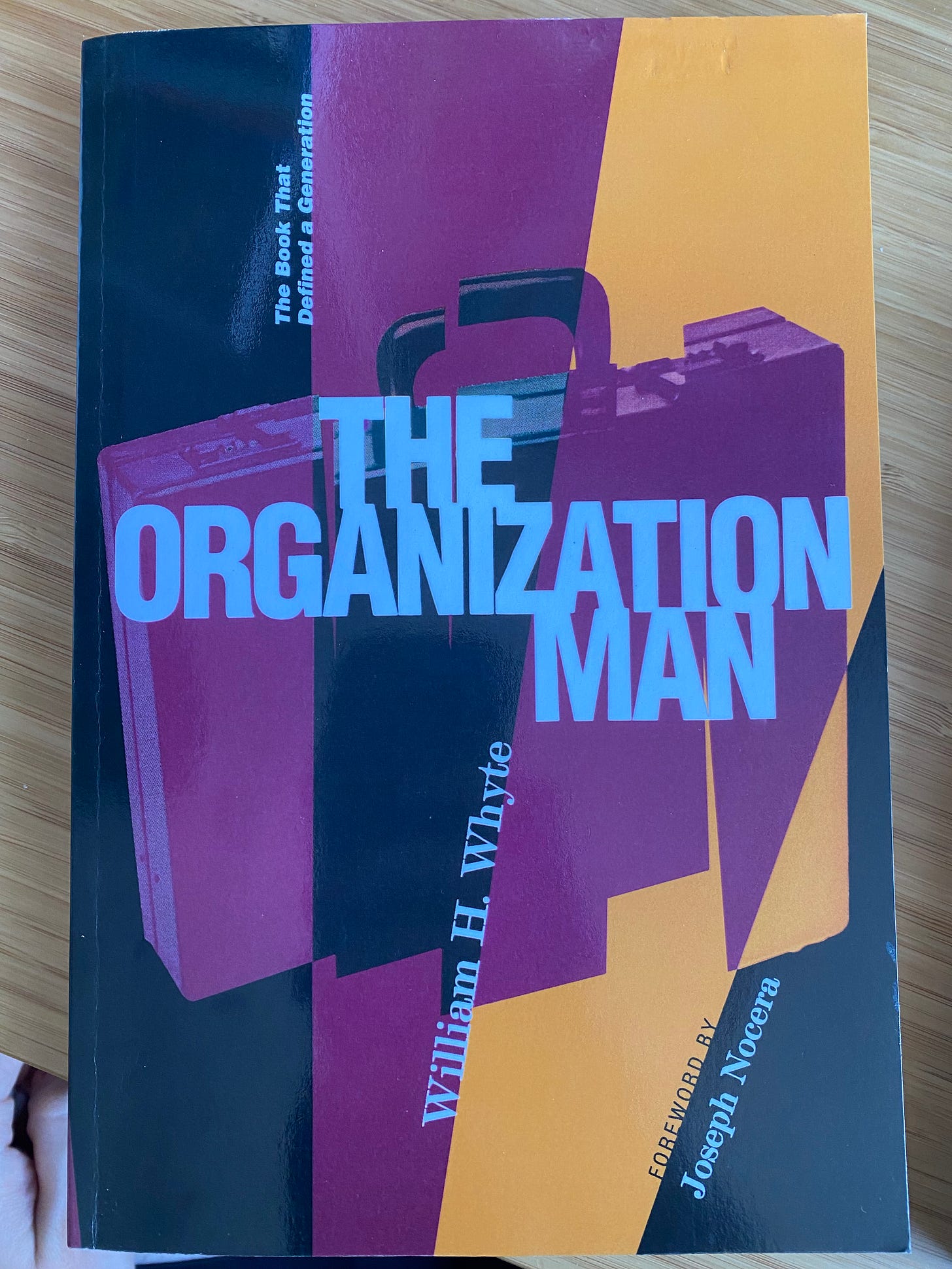

He's the author of another profound book, The Organization Man, which came out in 1956.

One could start to wonder: how are these books connected? Are they part of the same intellectual tradition? Did these authors know each other?

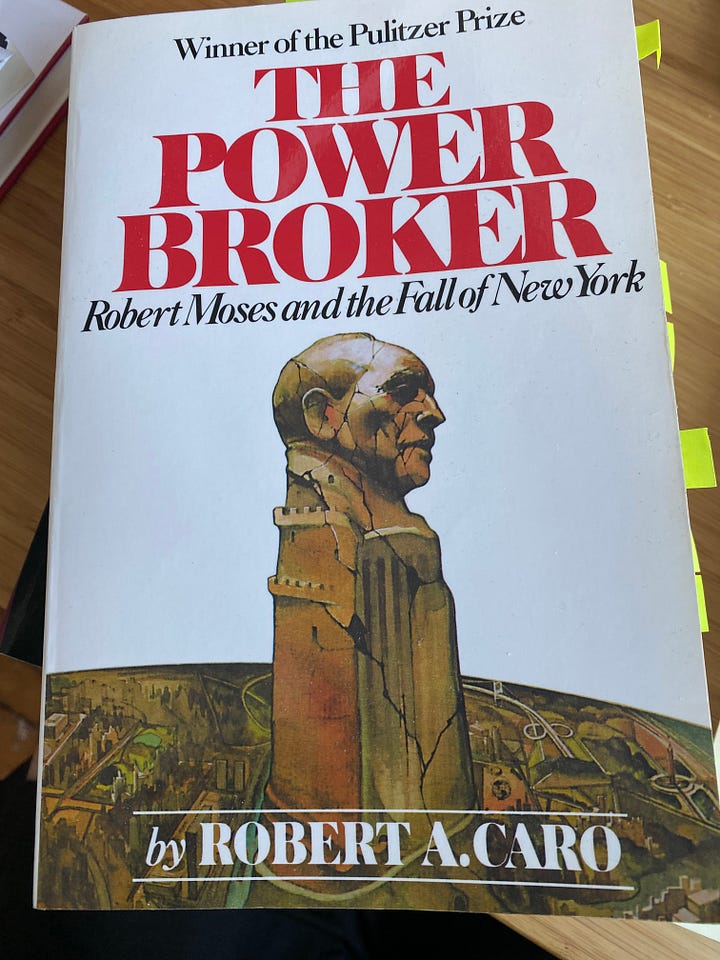

Or fast forward to 1974, when The Power Broker, by Robert Caro, came out. Take a look at the fifth blurb from the top inside the cover, and you find Jane Jacobs.

You can keep doing this forever, reverse engineering social and intellectual webs. Of course, a research project requires corroborating sources to nail down connections. Publishers source blurbs in all kinds of ways, not just from intellectual compatriots.

But if you've read The Organization Man, Death and Life, and The Power Broker, and then you notice the liminal connective tissues they share, you'll start to notice even less liminal, more robust through-lines in their ideas.

And personal libraries make liminal investigations like this much easier, not just logistically (you have the books right with you), but cognitively, because you’re staring at all of them together. If your library also functions, in part, as an antilibrary,2 this also motivates you to explore books you haven’t read.

You might even find that the books you first grouped by some idea texture or vague theme are also liminally linked! Interesting! Why is that? Libraries are their own ecology that provoke scientific curiosity. They create related systems of thought that you can then investigate, which is an emergent, complex quality of some libraries depending on how they were constructed.

But this isn't an essay about the three books mentioned above, or even how to do a syntopical comparison of them.3 I just wanted to show how books offer much more than their authored words, especially when they’re arranged in a library. It's that extra material that can supercharge curiosity, research, and rabbit-hole exploration.

Libraries are burdensome bricolage

You can collect books in the same ways that you collect other things: haphazardly, as unwanted gifts, slowly-but-surely over time in a way you never intended.

Many people often find themselves standing in front of shelves or boxes of books they don’t know what to do with. It just hits you one day that they are clutter, and that they are so much clutter. Sometimes they’re your books, and you’re moving homes or rearranging things. And sometimes they’re the books of a parent or grandparent who’s downsizing or passed on.

And doing something with libraries is rarely easy. Do you want to donate the books? Well, where do you take them? Do you need to sort them somehow?

Do you want to keep them? If so, how and where do you best arrange them?

Do you throw the books away if you can’t, or won’t, have them? For a variety of reasons, most people have immense psychological issues trying to do this, even if they do it eventually, and even if it’s the sensible thing to do.

And how do you move all the books? They are so heavy! Shipping them anywhere costs so much!

Maybe you can’t get rid of your books for one reason or another, but you feel shame for not having read them.

In so many life contexts, personal libraries are a burden to the people responsible for them.

Libraries are decoration

It’s no surprise that many people have libraries for decoration. In fact, they decorate a space even if that is not their direct, intended purpose.

And it doesn’t matter if you read the books you have; they are wonderful ornamentation. Like movie posters, album covers, or certain other kinds of art, they evoke variety! Not just of ideas, but of times, places, colors, and physical things. There is hardly anything more attractive to a human than a wall of variety laid out for their perusal.

How many times have you walked into someone else’s home and beelined straight for their bookshelf? For me, this is always instant and inevitable. What’s in there? I always wonder. In the first instance, I’m not even looking for anything specific. I just want to explore.

Some people arrange their books by color, or on angled shelves! Whenever I’ve seen these kinds of things done well, it’s always been a fantastic visual display.

But decoration isn’t simply about variety. We decorate and adorn to remind ourselves of things that we value.

Sometimes we keep books like we keep portraits of friends or loved ones who are no longer with us for any number of reasons (death, estrangement, natural growing apart). Maybe you read a book once and it was developmentally important to your life at the time, but you’ve moved beyond that strict utility. But it’s still important to you because it played a part in your personal journey that you don’t want to forget.

In this vein, we keep books we either haven’t read, or have read and largely forgotten, because they help us tell a story to others when they see our bookshelves. They are signposts that remind us of our own life’s plot.

Sometimes decorate with books because they are a great comfort. They are the closest thing we have to a grand convocation of minds, living and dead, of cultures across the world—of people. Their titles and spines summon all of this. Their physical form absorbs and pleasantly dampens sound in any space. Their inevitable smell, identifiably physical but not quite organic, is the same ancestral olfactory comfort as petricor.

When laid out like this, of course libraries are used as decoration. They’re so perfectly suited to it in so many ways.

Books-as-non-literary-decoration are sometimes conflated with deceitful social signaling

But some people don’t like the idea of books as decoration, especially if the book owner has not read, or does not intend, to read them. There are two things I have to say about this attitude:

First: sometimes people will deliberately put up books that they want others to think they’ve read, even if they haven’t. This is a common phenomenon, and it is deceitful. It is stolen valor. But that’s not using books as decoration, that’s mendaciously using them as a social signal. One of the reasons people get upset with books-as-decoration is because they’re conflating all versions of a personal library into “collection of books I’ve read,” so they interpret non-literary, decorative book uses as a violation of the concept. But, as I mentioned at the top of this essay, libraries are many different, valid things.

I don’t highlight the deceitful display of books primarily as an external chastisement delivered by me (or anyone) to another party, although it obviously is that. I am primarily concerned about the internal feelings of someone who uses books to lie like this. There are fewer surefire ways to engender feelings of imposter syndrome, fragile confidence, or aggressive defensiveness than to claim more knowledge about something than you actually possess. Using books like this will corrupt your character in ways you probably don’t want, and make you feel bad!

Second: the intention of a library owner determines a lot about a library, not just the fact of them having read their books or not. If you haven’t read your books, either because you like them for different, decorative reasons, or because they’re in your antilibrary, that’s great! If you haven’t read your books, but you want people to think you have, that’s probably not good.

These complicated, overlapping potentials for a library—in both personal intention and terminal goal—make people have conflicted feelings about companies like Books by the Foot (a company that I think is wonderful). Books by the Foot will prepare shelves of books for you in many different styles and/or intellectual valences, as you can see if you visit their site. During the pandemic they received a giant boost in the market and the media, because people began using them to stock the bookshelves that appeared behind them on Zoom calls (sometimes called “credibility bookcases”).

Clearly, there is potential for both deceitful social signaling and superb decoration here. But it is both and more than that, and Books by the Foot has other things to do with their time than administer morality tests (that would be dubious anyway) to their customers. Books by the Foot “…is designed to keep books alive. Our Books by the Foot service has given a second chance to millions of orphaned and otherwise unwanted books.”

Libraries are an unreliable proxy that are sometimes used as if they are reliable

“If you go home with somebody and they don’t have books, don’t fuck them.”4

If you haven’t heard this phrase, which is relatively common on the internet, you’ve heard it now.

The charitable idea behind the phrase is something like: “Use the presence and content of a personal library as a proxy for a good kind of critical and expansive thinking, and only physically gift yourself to those who probably, via that proxy, possess the proxy’s referent.”

In practice, I think the idea is often not very workable,5 mostly because of the thing I keep hammering: personal libraries fulfill many legitimate purposes, and many of those are not strictly about reading the books or being intellectual.

Further: people lie about having read their books, or they read their books so long ago that they can’t materially recall what they’re about; one easy-to-spot case of the latter is a set of books that are clearly from someone’s college days, for reading they never did, from a major they’ve long forgotten.

Further still: many people are bad at reading beyond a basic level. They don’t understand it as a composite skill, and therefore don’t improve their ability to do it. This means if they did read a book that they possess, even if they did it recently, they might not have done it in the way for which the book’s presence is supposed to be a proxy.

The furthest: maybe someone reads quite a lot, but they do it digitally. Maybe they write quite a lot. Maybe they record great conversations with discerning people and post those on the internet. There are many demonstrations of a good mind at work, I just think there tend to not be very many good, quick proxies that confirm that it is indeed a good mind at work.

The upshot: having books isn’t a good proxy for determining something about the nature of someone’s mind, especially in the scenario where you’re trying to discern something important about a person from a glance at some shelves; there is too much noise in that signal. You really have to talk to someone about their books, their ideas, and more to begin to get a good impression of their mind. But if you’re doing that, you’re not really using the presence of the books as a proxy anymore. You’re going after the proxy referent directly.

And, personally, I have been in the “go home with someone” scenario with enough men to know that bookshelves are bad proxies.

Personal libraries are so very human

They come in dazzling varieties, are built with highly variegated intentions (both between and within individuals), and serve many different purposes. I am inclined to enjoy them by default.

Our feelings about personal libraries sample the whole spectrum of feelings we have about people generally, many of which I didn’t even touch in this essay. And some people don’t even care about libraries in any fashion.

But I hope you have one that you love. I hope books ornament your home. I hope you’ve walked up to someone else’s library, and seen a collection of books that makes you suspect you’ve met a best friend, or a spouse. I hope you’ve gotten to experience personal libraries for their beauty, their intellectual delight, and their capacities as memorials to yourself and others.

😱, if you know, you know. The contents of this book comment on a city that, in many important ways, doesn’t exist anymore, at least not the way Jacobs thought of it. When thinking about Jane Jacobs, it’s useful to think about the world she saw and wrote about in Death and Life—it was a world before NYC’s 1961 Zoning Resolution, with its incredible downzonings and other regulations, fell on the city. It was a world that still had the Board of Estimate. It was a completely different world than NYC in 2023, legally.

From the Wikipedia: “The term antilibrary was coined by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his book The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable to describe the books that many people own but have not read. Taleb argued that such collections of books make people more humble and curious.”

In his (originally 1940) work "How to Read A Book," Mortimer Adler introduces the idea of syntopical reading, reading and comparing multiple books that are relevant to the same question. Examining the liminal connective tissue of your books (publication dates, blurbs, and more) both provokes questions and suggests which books are relevant.

The internet attributes this quote to John Waters, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s a fake attribution that just got attached to him. Regardless, it is a known phrase that people say!

Although there are a few exceptions. If you go home with someone and they have wall-to-wall shelves of a religion’s theological texts, or some presentation of equal magnitude, you can assume some things about them. Although maybe they’re a secular scholar of that religion! You’d have to use something other than the books to confirm that.

I definitely think a library is part of the style and prepared environment of the home. Having children makes this more apparent. Compare:

“When I was growing up my parents were always reading on their phones”

“When I was growing up my house was full of books and everyone was always reading”