Every culture has its stories, or a mythos: histories, myths, and mixtures of the two. The American founding and the Greek pantheon are classic examples, and in modern times Harry Potter has escaped the lab and integrated itself into our broader culture as well. In other words, Hades was a Slytherin.

If you have a sufficiently developed culture, it’ll have such a profusion of stories—the mythos will be so expansive—that anyone will be able to find themselves in a narrative. This is the story’s great benefit: it provides life blueprints, morality tales, speculative future projections, inspiration, warning, and more. All you have to do is a bit of pattern matching to see how a story can help guide your own life.

And while American culture writ large has no shortage of stories, its gay subculture certainly does. The results:

“What and how it is to be a gay man” is limited to a narrower set of cultural archetypes and narratives that negatively influence how many gay men see themselves, and how they’re viewed by others.

Many gay men cannot pattern match themselves into gay culture, and must look elsewhere for belonging and inspiration (this isn’t to say that every subculture must carry every narrative—but a subculture as large as the gay one should carry more).

This narrative impoverishment must be remedied. The pantheon must be filled.

The mythos of traditional gay culture

Traditional gay culture1 has tons of stories, and they’re generally variations on two themes:

First: the struggle. Overcoming persecution, prejudice, and hardship. An example of a sub-theme here is “chosen family,” an adaptive cultural response to ostracism.

The struggle’s place as a dominant story makes sense: gay culture in the U.S. has really only existed for about fifty years2, and was born exposed on a hill during a thunderstorm. Struggle permeates gay culture because that’s mostly what it was for a long time, in varying kinds and degrees.

These stories are valuable, and they have an important place in any culture. Among many things, the trials of others help you feel less alone in your own, and when given narrative wings can be a potent catalyst for change.

Second: the redemption. Hitting rock bottom and then rebounding to live as a well-adjusted gay man.

The redemption story is, in many ways, a complement to the struggle story; they often overlap. After all, it is the hardships of growing up gay that have driven many gay men to self-destructive behavior in the realms of sex, drugs, and sociality—from which they then rebound. A now-quintessential example of this is the book The Velvet Rage: Overcoming the Pain of Growing Up Gay in a Straight Man’s World, where the author recounts his own (and others’) long, difficult road to living a happy life as an adult gay man.

Like struggle, redemption is a good cultural feature. It pulls men back from the brink, gives them hope that their life can be restored, and calls others to lend a helping hand. It permits room for mistakes and error.

And yet, the dominance of these two stories in traditional gay culture produces a whole host of problems. To be clear: the stories themselves are not the problem. It is the fact of their duopoly, the comparative absence of other stories, that produces the problem.

Together they create a culture that is primarily about fighting an enemy, and they produce an expectation of suffering. I ask you: are the greatest people the ones who define themselves against their enemies—or are the greatest people those who act as their own standard? Are the greatest cultures those that give their pantheon’s throne to suffering, or to joy?

Traditional gay culture has a mythos deficient in unalloyed glory, honor, moral ambition, and light. And while understandable, given its origins, this is no way for it to continue into the future.

The new stories of an ascendant gay culture

So what do I propose? What stories should be told? I think three archetypes are in order:

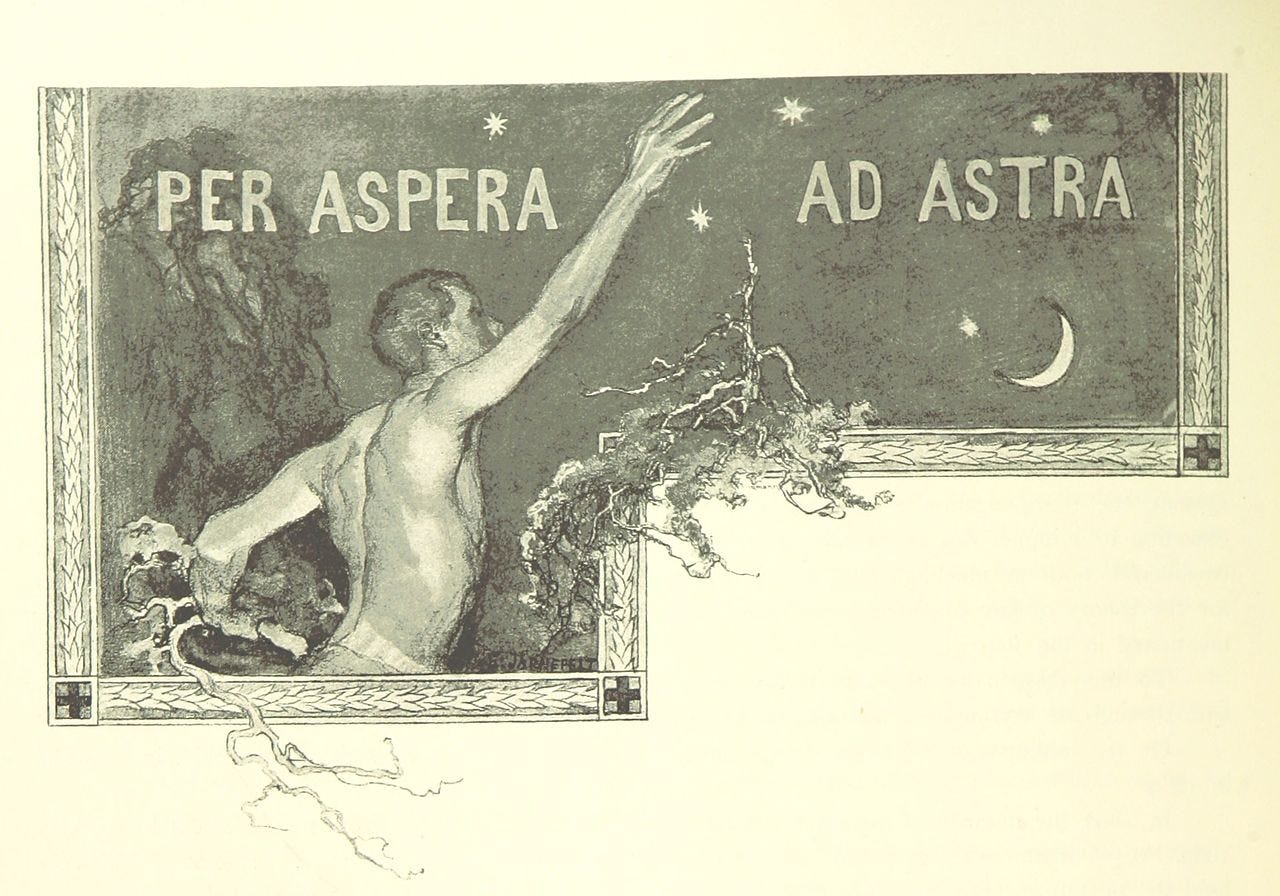

First: the navigator. The man who saw every wrong turn, and went the other way. The one who was never in danger of rock bottom, because he was too intensely occupied following the North Star. Why repeat the mistakes of many others when they’ve all been written about and warned against? Why stare into the black depths when there are gleaming stars overhead?

There are multiple human responses to suffering and hardship, influenced both by individual character and external events. Sometimes the response is collapse, but often it is blazing resilience, psychological fortitude, and sufficient self-confidence to avoid the worst decisions in the first place. The navigators deserve to have their stories amplified. They show that proper action and right direction are more possible than we might think.

Second: the earnest man. He is guiltless, un-self-deprecating, and boldly owns that which he holds dear in a culture that otherwise prizes witty insincerity.

While he acknowledges the horrors that gay men have endured in the past and present, he does not offer these nightmares an emotional tithe. He states his ambitions for a better present and future plainly, and regards the cultivation of character and physicality to be unambiguous goods.

Third: the frontiersman. He might also be called an Atlantean, and he wonders: if gay men can be regarded as masters of art, why not everything else? Gay men are known for superior talents in dance, music, and performance. But that culture of excellence can broaden to include gay men establishing lunar colonies, founding new cities, writing superlative philosophy, boosting gene therapy, and pushing the limits of manufacturing.

The frontiersman sees gay culture, among other things, as a fraternity of the glorious attempt. He sees the gay man as the man in the arena.3

In the cultural pantheon, the navigator, earnest man, and frontiersman should be preeminent, with the frontiersman first among equals. When young men come out, they should feel the strong embrace of a culture that unabashedly thinks the world of them, that regards them as vital stewards of a human golden age.

Getting from here to there

The archetypes that I want to diffuse throughout gay culture center achievement, glorify attempts at it, and celebrate each operating at his own capacity toward noble goals.

To some, these stories might feel like a rebuke. When I’ve outlined my vision to men before, I’ve heard many variations of, “But won’t centering [greatness, those who made great decisions, those who avoided self-inflicted pain, those who dream of stars] take attention away from men who are suffering? Doesn’t it judge these men harshly?”

You don’t have to get rid of redemption and struggle in order to center the navigator, the earnest man, and the frontiersman. They all belong, but these last three are what give a culture positive meaning and demand its best.

The stories a culture tells matter.

You do not have to deny help and recognition from the man who has fallen in order to applaud the achievement of others. In fact, the former is best given to a man so that the latter can be given to him later.

See my definition of that term, and expansion on what “traditional” means, see here: “Definitions: For my purposes here, ‘community’ means a specific collection of individuals united by social ties, and ‘culture’ is the ideas and behavioral norms that prevail in that community. The use of ‘culture’ in this essay necessarily means ‘culture, and the community it derives from.’ Similar with ‘community.’”

I use the late sixties as an approximate starting point for modern, coalesced gay culture in the United States. I can image others would put the origin in different places, but I think most would agree it’s after WWII, and before the seventies.

“It is not the critic who counts: not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles or where the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes up short again and again, because there is no effort without error or shortcoming, but who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, who spends himself for a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows, in the end, the triumph of high achievement, and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who knew neither victory nor defeat.” —Theodore Roosevelt from his speech “Citizenship in a Republic,” delivered at the Sorbonne in Paris on April 23, 1910.