Abjure Comfort, Pursue Good

Happy New Year, friends. 2022 will be uncomfortable, but the optimal amount of discomfort is not zero.

I spent the majority of December 2021 in Cambridge City, Indiana, for Christmas, near the farm where I grew up. In addition to enjoying every second of time spent with my mother, I was reminded of one principal reason why I choose to live in Manhattan: I like living in a culture that regards walking as a normal and primary mode of transportation, and everything that comes along with that.

It’s not as though the small towns of my erstwhile youth aren’t walkable; it’s that people are so used to driving everywhere that they have blinded themselves to walking when it’s an option. The difficulty is not usually infrastructural, but cultural.

Cambridge City is only 1.5 miles across, and one square mile total. For many of its ~1,700 inhabitants, a nice coffee shop, several restaurants, a grocery store, a post office, a gas station1, several churches, a school, a (good) gym, and a collection of perhaps ten other stores are all within a 20-minute walking radius; if you have a bike, the whole town is trivially within your reach. Nonetheless, its sidewalks are perpetually empty. I was almost always the only person walking around, and when there were other people, they were leaving or entering a car parked right outside their destination.

Why don’t people walk, despite the good option to do so?

The False Good of Comfort

People prefer driving in Cambridge City (and most places), because it is comfortable. You walk from your climate controlled house into your climate controlled car, and from your climate controlled car to your climate controlled destination. All while only taking a few steps!

If you were to walk, not only would you have to spend more time getting from one place to another, but you’d have to expend the energy to walk there; and it’s not like exercise makes you happier, or feels good, or provides any number of benefits to your well-being.2 Maybe the weather is a bit too hot or cold! Or maybe it’s raining! So many things could cause your body to deviate from 98.6 degrees, so many things could raise your heart rate even slightly. The human body and mind surely cannot withstand such abuse, and certainly not benefit from it. Walking is not comfortable.

If you’re thinking “Daniel’s gettin’ a tone about this walking stuff,” you’re right. Because it’s only one particular instance of a larger, terribly wrong idea in our culture, that, despite my Indiana-specific example, pervades most domains of our Fair Columbia: comfort is good, discomfort is bad.

The Illusion of Equilibria

Discomfort is the feeling of deviation from an equilibrium point, for good or ill.

Comfort is the equilibrium point. It could often also be called homeostasis. It is a resting place to: (1) recover from, and bask in, the exertions of good discomfort, and (2) heal from the injuries of bad discomfort.

In fact, “comfort” and “discomfort” would better be thought of as “equilibrium” and “non-equilibrium.” Why? Because our culture overwhelmingly conflates “discomfort” with “bad,” and this connotation destroys and deadens lives.

The bad forms of discomfort are obvious. If you eat too much and get a stomachache, you’ll want to return to the equilibrium of feeling regular-full or no-hunger. If you go to the gym for the first time ever on January 1st and try to deadlift your bodyweight, you’ll soon want to return to the equilibrium point of no-back-pain. And if you get sick or physically age past your point of optimum maturity, you’ll find out those aren’t good departures from equilibria either.

But there are also good forms of discomfort, good departures from the equilibrium. In fact, it is these forms of discomfort that produce every good thing that humanity has, and that make each individual strong, moral, smart, and safe. These discomforts are things like physical activity, thinking, learning, cultivating skill, and daring to speak when no one else will. All virtue, all glory, all progress, and all good are born of discomfort—a departure from the equilibrium point.

And equilibrium points are not static! They move based on what you do, or don’t do. If you regularly exercise, your equilibrium energy levels (and happiness, etc) will be higher. Every good discomfort you embrace is a small tug that pulls your equilibrium point—your baseline—to a better place. This allows you to shoulder even more discomfort relative to your original starting point.

Unfortunately, the exact same is not true of falling equilibrium points. While pursuing destructive, ruinous behavior will pull your baseline down…

…so will doing nothing, if you make it a habit! If you don’t pursue good discomfort, you will slide, by default, into the bad forms of discomfort, only to fleetingly gain refuge in desperately grasped-for equilibrium; to such an extent as you allow this mentality to take over your life, you will only ever flee from pain, never to taste achievement or goodness.

Without embracing good discomfort, humanity would be nothing other than an animal more aware of its suffering than the others. This is true of the species, and of each of its individuals.

If you do not embrace the discomfort of strength, you must endure the discomfort of weakness.

If you do not act through the discomfort of courage, you will suffer the discomfort of cowardice.

Comfort is not a neutral or permanent state. It is the average of the kinds of discomfort you have chosen3. Your equilibrium is defined by its deviations.

The First Million is the Hardest

To go from $1 million to $2 million…requires 100% growth, but the next million after that requires only 50% growth (and then 33% and so on). —from Investopedia

Many people have heard the phrase “the first million is the hardest,” and I think it’s pretty easy to understand why this is true. Not only do you have to overcome startup costs in your life (paying off student loans, spending money on various mistaken life paths, etc), you have to take time to build up the first million itself. But after that point, the power of compound interest makes it much easier to earn further millions.

This is true with the values and virtues that come from pursuing good discomfort. Let us consider exercise: the first time you do it, you will be at your weakest. Your body won’t be able to handle much strain, your cardiovascular system won’t be able to shuttle oxygen around that well, and your lizard-brain will shout at you to stop because you must be dying.

But, as you exercise more, your body gets used to it. It adapts slowly, until at some point—after you’ve “made the first million”—you find that you enjoy exercise, and your body wants it. After that point it just seems easier and easier to be more active, and to branch out into more kinds of exercise and physical activity.

But:

…compound interest doesn’t only work in our favor. Anyone who has held debt knows this.

Compound interest also increases the amount of money you owe on any loan, especially as the term of your loan gets longer. And, compared with savings and investment, it’s much easier for most people to stumble into an adversarial relationship with compound interest via credit cards, students loans, and other instruments of consumer debt. —from my personal website

Just as compound interest can help, it can hinder. Just as a habit of good discomfort makes doing harder things easier (and then pleasant!), a habit of bad discomfort will make doing things harder (and then worse!). You do not want to find yourself on the business end of exponentiation.

Now, you might be wondering what a habit of bad discomfort is—who willingly chooses to feel terrible all the time? I don’t think many people do that directly. But they do try to avoid pain—and claw their way to comfort—through behaviors that are short-sighted and ultimately destructive.

Instead of thinking through uncomfortable things or facing hard truths, people pursue mind-numbing substances4. Instead of cultivating their physical form, people eat bad food and do not move. Instead of investing in friendships over time, people isolate themselves. Instead of figuring out what a worthy use of their life would be, as my friend Étienne wrote, people build Rube Goldberg machines. Instead of cultivating their own tastes, people give themselves over to the fashion of the crowd for its fickle approval.

Instead of walking…people drive.

Take Leave of Your Equilibria in 2022

The New Year is perhaps the most disappointing time of the year for people, because they fail to actually embrace good discomfort—they cannot “make the first million” and come out the other side.

Many fail because our culture, prizing comfort above discomfort in almost all domains, does not lay out proper default paths for everyone to follow. So those who do want to be fit, think better, eat well, love with passion, and disagree with equanimity, must figure out how to do it themselves from scratch, often in an environment that actively works against them.

BUT! This does not mean anyone should give up. Now more than ever, it is easier to “find the others.5” That is, find the others who insist on being great to the best of their abilities, who understand the necessity and virtue of good discomfort, and who lament the unfortunate state of having to bear the burden alone:

If you want to disturb work equilibria, follow Paul and buy his new book (in the link).

If you want to learn self-love and leave our culture’s default state of forever-perpetuated, fashionable mental illness, follow Sasha.

If you want to find a group of intelligent, thoughtful people to survey the world with, join the Interintellect.

For all other things, just email me for suggestions. I can happily say that I know people in every domain I can think of who successfully threw off the tyrannous yoke of the comfortable default.

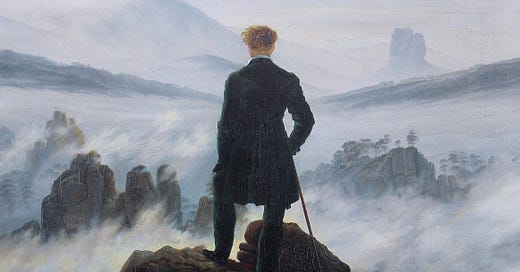

Discomfort not only leads to good things, but it allows you to truly appreciate comfort when it comes to you; not in any abstract way, but on a visceral level. Further: the true power and glory of human equilibrium blooms most in the throngs of discomfort.

When I run into the wind and cold along the frozen Hudson, towering Manhattan at my side, I’m shielded from the elements by a slight halo of cultivated animal vitality—the thin veneer of heat from the homeostatic impulse.

Happy New Year, friends.

If you’re wondering why you would walk to a gas station, then you have perhaps never lived in the rural interior. You walk there to get snacks, fountain drinks, and cigs. Duh.

“Exercise gives you endorphins. Endorphins make you happy. Happy people just don't kill their husbands, they just don't.” —Elle Woods, Legally Blonde

Obviously some discomforts are thrust upon us without our permission. Congenital disease, random bad accidents, aging, etc. But the fact of this excuses no one from agency, from doing the best they can with what they have. It is most often the people who have the least imposed deviations that use the idea of them as cover for why they shouldn’t be expected to embrace discomfort.

Alcohol is probably the worst, even more so because its evil is socially accepted. I’m not a teetotaler, and I think alcohol should be legal, but it is an infernal scourge on our society, and our culture has the exact wrong attitude toward it.

In Brené Brown’s book Braving the Wilderness, she says that leaving the default path of society can be scary, because you have to walk out into the unknown wilderness yourself. But there is a reward for this bravery—they find that the “wilderness” is actually filled with others just like them. My note: a comfort-obsessed culture will look at an open space of adventure and opportunity and call it either wilderness or barbarous.

Curious how you fit together the Deep Okayness Sasha writes about and the premise of achievement beyond comfort you write about. I can see a way, but without its articulation the idea of striving in discomfort *and* feeling genuinely OK with where and how you are seem incompatible.

Also:

(1) Oof: “or physically age past your point of optimum maturity”

(2) Lol: “You do *not* want to find yourself on the business end of exponentiation.”

I really like the normalizing effect of bad/good for comfort and discomfort. I also like the distinctions between discomfort. A young me always jumped to the equivalent to deadlifting body-weight for the first time in the gym whenever I tried to pursue discomfort.

“Discomfort” does not feel bad if we dont anticipate it and try to resist it. It feels like a small fire that one can tune up and down depending on activity. At the end, the right fire creates a new desired equilibrium.

Lovely essay, looking forward to meeting you at the end of the month to learn about American revolution history!